This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the tactics, behaviors, and operational patterns of North Korean (DPRK) IT workers operating globally under false identities. Leveraging platforms such as GitHub, Telegram, and freelance job boards, these actors have demonstrated increasingly sophisticated methods to secure remote employment, often in violation of sanctions.

Key findings highlight how DPRK operatives manipulate online ecosystems to bypass identity verification, exploit remote desktop access, and deploy proxy infrastructure. GitHub serves not only as a technical collaboration space but also as a medium for reconnaissance and persona building. Communications , including Telegram chats, offer rare insights into their techniques and coordination.

Case studies, such as the AssetX scam and grant applications on Polkassembly, underscore the strategic intent behind these operations, often aiming at financial gain and resource extraction. The report concludes with actionable mitigation strategies, behavioral indicators of compromise, and broader implications for national and organizational cybersecurity.

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Strategic Overview

- 3. Profile Engagement & Behavioral Attribution

- 4. Direct Engagement with “Motoki”

- 5. Communication via Telegram

- 6. Tactics and Methods to Circumvent Restrictions Observed in Both Interactions

- 7. DPRK IT Workers Behind AssetX Scam: Applying for Grants on Polkassembly

- 8. Conclusion

1. Introduction

The activity of DPRK IT workers has been persistent across multiple job search platforms. Additionally, GitHub has emerged as an ideal environment for these actors to organize, interact with one another, and conduct reconnaissance on their intended targets. A significant portion of DPRK IT operations have also concentrated on open-source and freelance platforms, which enable them to craft convincing people and, in many cases, bypass KYC (Know Your Customer) procedures and successfully navigate interview processes.

Given the differentiated behavioral patterns observed across various platforms, several indicators on GitHub have facilitated more accurate identification of DPRK IT workers. Notably, the correlation between their GitHub activity, personal details, and in many instances, traces of personal interactions and habits, has proven to be a key factor in attribution and cluster analysis.

2. Strategic Overview

The sustained infiltration of Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)-affiliated IT personnel across digital ecosystems—particularly code collaboration and freelance marketplaces—represents a significant and evolving threat vector within the cyber threat intelligence landscape.

These actors exploit platforms such as GitHub not only for technical collaboration and community engagement but also as reconnaissance surfaces to identify and monitor potential targets. GitHub has become a high-value operational node, enabling DPRK-IT Workers to discreetly coordinate activities, cultivate convincing developer personas, and distribute technical assets.

Likewise, gig economy platforms and open-source repositories serve as effective camouflage, allowing these operatives to pose as legitimate contributors. By deliberately shaping their profiles, actively contributing to repositories, and leveraging peer interactions through social engineering tactics, they frequently bypass platform-level identity verification (e.g., KYC checks) and infiltrate hiring pipelines undetected

On GitHub, for instance, patterns in repository activity, account metadata, avatar reuse, contribution timing, naming conventions, and social graph interactions (followers/following behavior) have enabled increasingly confident attribution. In certain cases, these patterns correlate with off-platform communications and linked auxiliary accounts, shedding light on operational intent and real-world affiliations.

This analysis synthesizes a broad set of open-source intelligence (OSINT) indicators—including screen recordings, chat transcripts, and GitHub account information—to enhance detection and response capabilities against DPRK-origin IT operations embedded in global digital environments.

2.1 DPRK’s Cyber Modus Operandi and Use of Open-Source Platforms

This investigation incorporated the analysis of several interviews conducted with Motoki Masuo, as well as personal conversations that provided deeper insights into:

- Recruitment methods

- Operational objectives

- Preferred work platforms

- Personal advice from the actors on improving job profiles

Between January and February 2025, active monitoring was carried out on multiple identified profiles. A series of structured interviews was organized with the objective of detailing their operational patterns and uncovering potential associations with other accounts, particularly on GitHub.

As a result, it was confirmed that Motoki operates as a DPRK IT worker, and further connections were established linking him to other previously monitored profiles on GitHub. These accounts were found to be actively working on projects primarily related to Blockchain and Web3.

3. Profile Engagement

Initial contact with Motoki Masuo occurred via Telegram on January 15, 2025. The alias was linked to the GitHub account:

GitHub: https://github.com/motokimasuo

- The GitHub account

MotokiMasuowas connected to multiple accounts under surveillance for suspected links to DPRK IT operations.

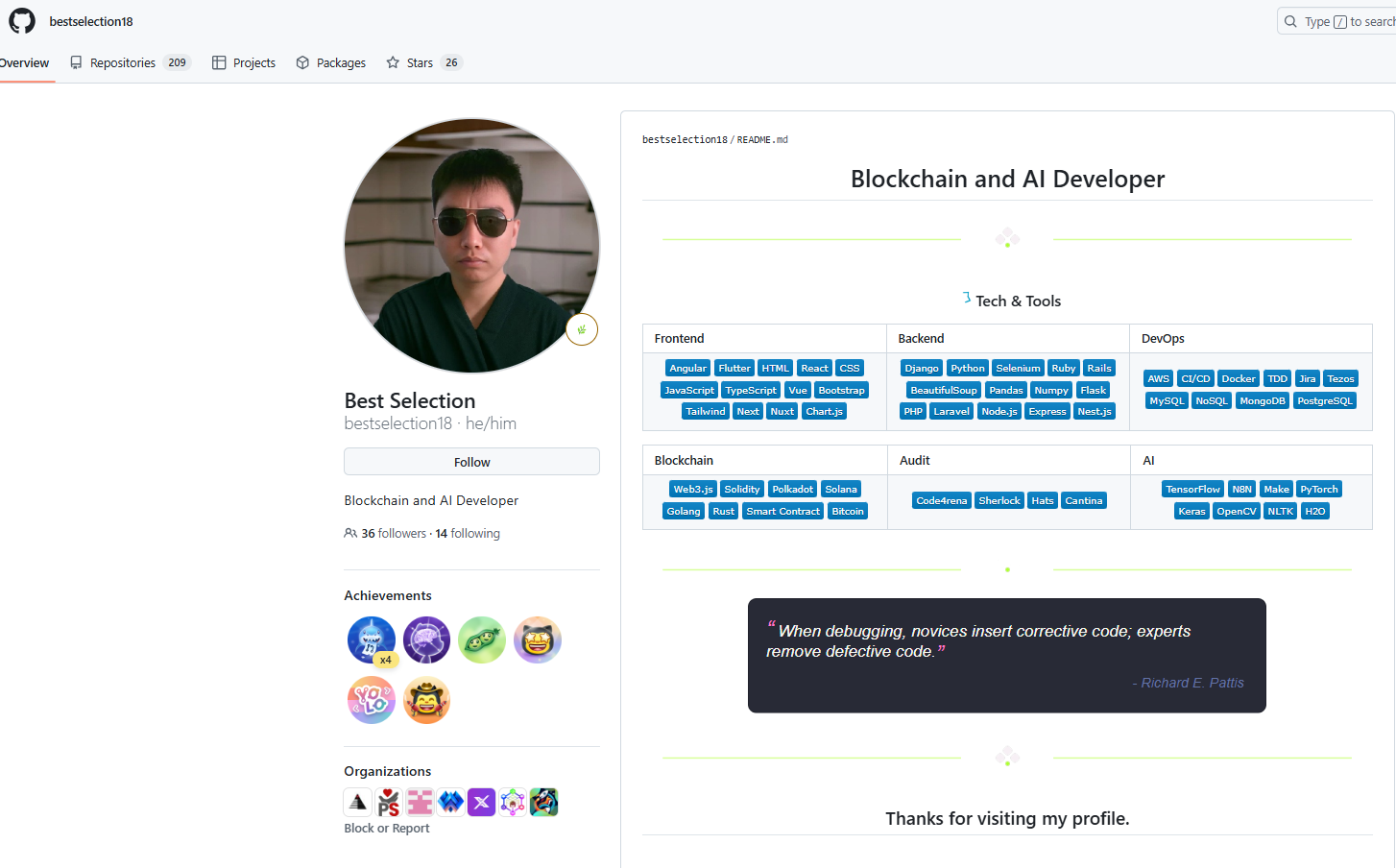

Among them was: bestselection18:

https://github.com/bestselection18 — previously reported for anomalous activities in GitHub organizations and DAOs.

4. Direct Engagement with DPRK It worker: Motoki

The engagement with the individual known as Motoki Masuo progressed, culminating in the first video interview conducted on January 29. The following day, the subject—claiming to be Japanese—attempted to validate his identity by sharing a document via Google Drive: link.

The initial exploratory interview provided corroborating evidence that the individual was not of Japanese origin, as previously claimed. Behavioral inconsistencies and metadata analysis confirmed that the persona presented was entirely fabricated. Notably, the GitHub account https://github.com/motokimasuo, which had been used for initial contact, was deleted days prior to the interview — an evasive maneuver commonly observed in threat actor operations.

During the session, Motoki joined the call and began by asking scripted questions regarding his own background and professional history. However, a critical operational security failure occurred when he unintentionally shared his screen. This exposed his login process into a Gmail account truepartner312@gmail.com — an address unlinked to the identity he had previously disclosed, further reinforcing the use of a false persona and layered alias infrastructure.

The interview lasted approximately 15 minutes and revealed several behavioral anomalies. The subject demonstrated difficulty articulating social and interpersonal experiences, along with inconsistencies when describing personal and professional skills. These behavioral indicators, combined with prior suspicious activity observed on his GitHub account, further reinforced the assessment that he was part of a known cluster of DPRK-affiliated IT workers.

Following continued engagement with Motoki, a second interview was scheduled for February 25. This session was to be conducted with the collaboration of a different interviewer, with the explicit goal of verifying the subject’s claimed fluency in Japanese—a critical step in validating or refuting his stated nationality and identity.

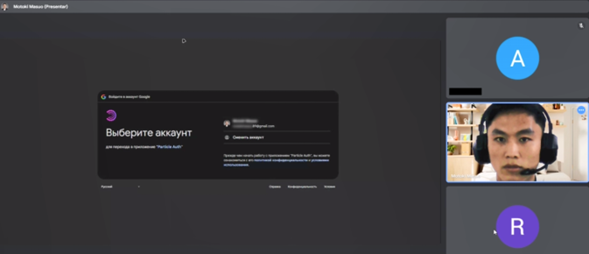

At the beginning of the second interview, the email address associated with Motoki appeared blurred on screen; however, based on the avatar and interface cues, it was identifiable as motosimasuo@gmail.com.

Interestingly, the default language displayed in their Gmail account is Russian, as indicated by the prompt Выберите аккаунт (Choose an account). This could potentially be influenced by the browser’s language settings or the geolocation of the IP address being used.

The interview continues with several questions directed at the candidate; however, most of their responses are repetitive and revolve around the same topic. The candidate appears unable—or unwilling—to share personal experiences or provide specific details about previous roles.

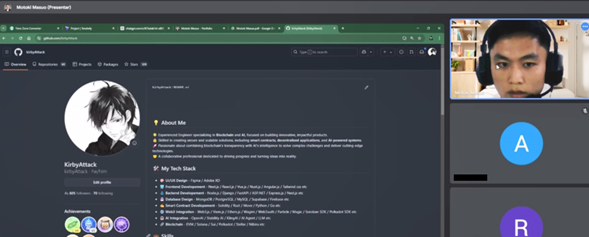

At one point, Motoki is asked to share their screen again; however, he used a different profile — github.com/kirbyAttack — as evidenced in the following image.

The interview proceeds, and since the user is sharing their screen, they are asked to access one of their GitHub projects. This allows us to confirm that the individual shares activity with a previously monitored account: Motoki – Hiroto. In the following video, both users can be seen interacting with a private repository named AssetX-dex-frontend under the profile, along with another user identified as bestselection18.

Returning to the final minutes of the interview—and after several key aspects had been confirmed—Motoki is asked to introduce himself in Japanese. After a brief pause, a collaborator in the interview, Yohan Yun from CoinTelegraph prompts him in Japanese by saying: ‘Please, introduce yourself.’ At that moment, the candidate removes his headset and abruptly ends the interview.

Following this incident, the interview concludes, along with all further contact with Motoki, who appears to have realized he was exposed. A primary objective of these interviews was to gather as much information as possible to identify and correlate additional actors engaged in similar activities, particularly those operating through GitHub

5. Communication via Telegram

Following the final interview with Motoki, and through a separate personal approach, we managed to re-establish contact with him via Telegram several days later after the last interview where he left the meeting and removed his headset. This renewed communication enabled to continue progressing with the investigation and to further pursue the objective of collecting as much information as possible.

Below is a series of conversations with Motoki that shed light on key elements of his modus operandi, as well as other important activities currently being developed internally

5.1 Highlights from Telegram Chats

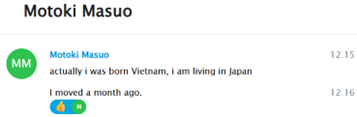

After several days, Motoki chose to respond to the Telegram chat and proceeded to share some ‘personal’ information. He claimed to have been born in Vietnam but stated that he had been living in Japan for the past month:

Over the course of several days, normal conversations were maintained with Motoki, during which he shared details about his recent interest in learning artificial intelligence. However, he also began to make comments such as, ‘If you have good skill, you can be hired by a company with a high salary,’ which raised concerns about his approach to interpersonal interactions and possible underlying motivations.

At times, Motoki offered advice on where and what to study. One notable mention was CryptoZombies.io, which he described as ‘fun’—a platform often used for learning smart contract development in a gamified way

He repeatedly recommended learning Solidity through this platform, emphasizing that it was easy to grasp—particularly for individuals like him:

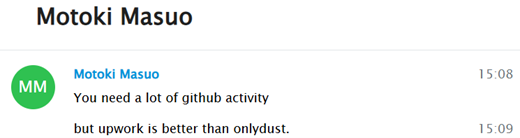

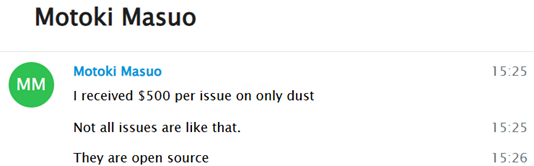

On the other hand, during these conversations, topics related to his previous activities emerged. This allowed us to further confirm that he—and other DPRK IT workers—had also engaged in work on open-source job platforms such as OnlyDust

He went on to confirm previously known information regarding the high number of individuals operating on these platforms and others, posing as developers. He also suggested that I could potentially find jobs there and secure a source of income.

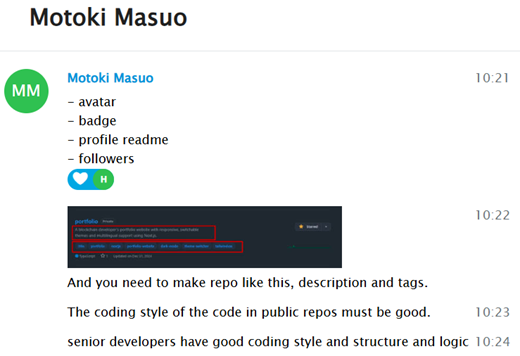

As the conversation progressed, Motoki offered advice on how to improve my GitHub profile—highlighting which aspects they consider most important for increasing visibility and credibility. These included setting a recognizable avatar, earning badges, creating a detailed profile README, increasing follower count, and adding clear descriptions and relevant tags to projects, among other elements:

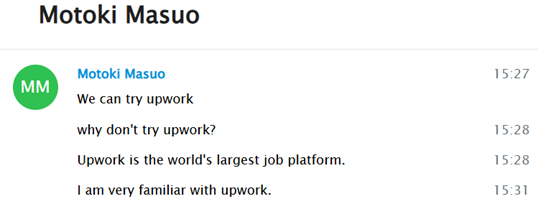

Additionally, he shared further advice on maintaining the right level of activity on GitHub to increase the chances of being hired. His suggestions reflected a clear focus on optimizing one’s public profile to appeal to potential employers. He also demonstrated a growing emphasis on platforms like UpWork, highlighting it as a key space for securing freelance opportunities:

He also reaffirmed details we had previously uncovered and reported to OnlyDust, though no response was received at the time. As a result, it is possible that additional DPRK IT workers may have received payments through such platforms, due to the lack of timely action or oversight:

5.2 Techniques for Job Access and Platform Manipulation

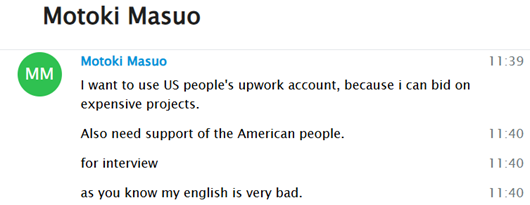

As previously mentioned, there is a noticeable preference among DPRK IT workers for platforms like UpWork. According to their own words, this is because it is considered ‘the largest platform in the world,’ making it a prime target for securing freelance contracts and blending in with legitimate global developer communities

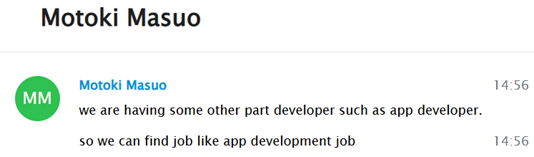

This intent was repeatedly emphasized throughout our interactions. Moreover, their skill sets appeared to be diverse. According to Motoki, it became evident that these individuals are likely in regular contact with one another and appear to be organized across various projects—including Blockchain, AI, and even app development—as confirmed by his own statements

Their involvement in app development is particularly noteworthy, as most activity previously linked to this cluster had been heavily focused on Blockchain-related projects. However, there was noticeable and persistent emphasis on platforms like UpWork. As stated in his own words, this was due to the ability to ‘bid on expensive projects,’ highlighting a strategic interest in high-value freelance opportunities

These and other statements reflect a clear economic interest behind these types of activities, prioritizing financial gain with the intention to cause direct harm. The following image highlights various strategies employed by these actors to gain access to job opportunities in the U.S., primarily through platforms like Upwork, which become access vectors to the U.S. digital labor ecosystem

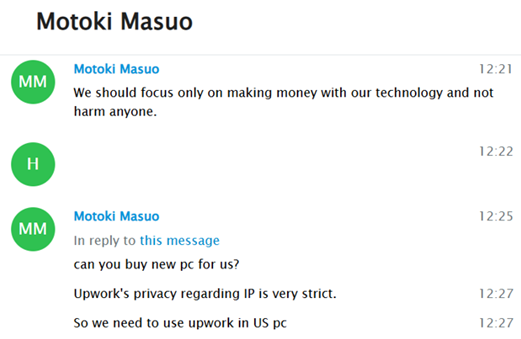

In this case, Motoki asks if I can purchase a PC for them, allowing them to remotely connect to the device in order to validate the IP location. A significant part of the scheme involves me buying the equipment, with the promise that they will either reimburse me later or, alternatively, they offer to send the funds upfront so that I can acquire the PC on their behalf, thereby enabling their access

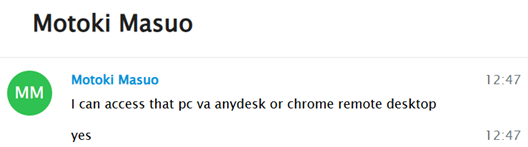

Given that Upwork has increased access restrictions, making it difficult to work even through VPNs, these actors have resorted to alternative strategies. One of their methods involves using remote desktop applications such as AnyDesk, allowing them to work from the victim’s device without raising suspicion or requiring VPN connections.

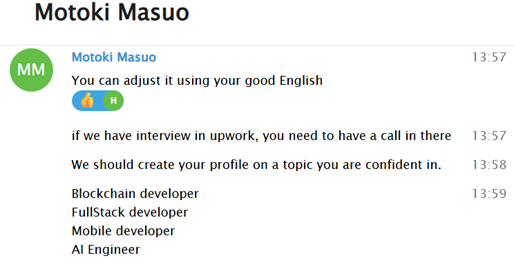

Another notable tactic involves them creating an Upwork account on my behalf, carefully tailored with skills I’d feel comfortable claiming. I would then participate in the interview process with their guidance, while in reality, they would perform all the work by remotely accessing my PC

These methods of accessing Upwork by taking advantage of someone’s skills to later carry out the work remain particularly difficult to prevent. Moreover, there has always been the offer of a “deal” regarding payment in exchange for allowing such activities through any of the methods mentioned above.

Given these tactics, it’s likely that many individuals could become involved in such schemes whether by purchasing a PC for the actors to use remotely, receiving corporate equipment on their behalf, or allowing them to connect to a device or your own for this purpose, as was suggested by ‘Motoki’.

Conversations with Motoki tend to be significantly more extensive, allowing for a deeper understanding of the individuals involved. These interactions often reveal personal insights and involve discussions that go beyond the typical technical exchanges related to ongoing projects or tasks, making these conversations particularly rich in qualitative detail.

6. Tactics and methods to Circumvent Restrictions observed in both interactions

Based on the evidence presented, it is possible to identify various methods used by DPRK IT workers. They employ a range of evasive strategies to bypass geographic and platform restrictions, especially on freelance platforms like Upwork. These tactics reflect a calculated and evolving approach designed to disguise their true location and identity, enabling access to global job markets.

As part of this, they have been observed recruiting individuals to attend technical interviews and client calls on their behalf, and promising financial incentives such as salary splits or freelance-style arrangements to make these requests more appealing and lower suspicion.

6.1 Tactics and methods to access jobs using GitHub

The interactions on Telegram with Motoki expose several tactics these individuals use to recruit others for attending calls, completing background checks, and using accounts they’ve created. In some cases, they even propose splitting the salary. The next interactions on GitHub corroborate these conversations with Motoki, presenting similar offers and outlining the strategies they intend to use to unlawfully gain access to job positions

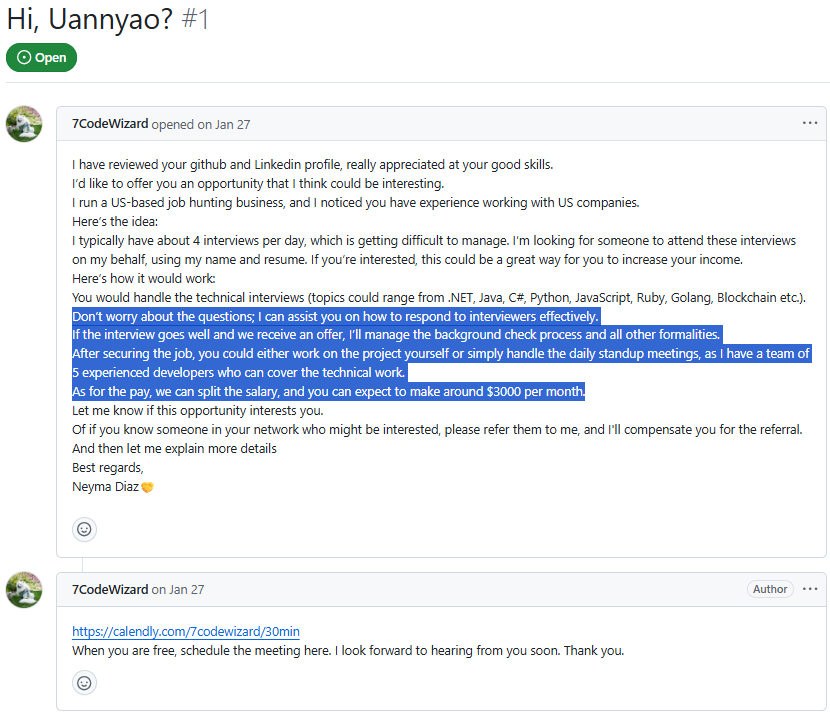

Similarly in the image, a user with the GitHub handle 7CodeWizard reaches out via a message offering a job opportunity. They explain that they manage a US-based job hunting business and are seeking someone to attend technical interviews on their behalf, using their name and resume. The account related to DPRK IT Workers reassures that they can assist the recipient in answering interview questions effectively:

If the offer is secured,7CodeWizard would handle the background checks and formalities. The compensation is proposed as a salary split, with an estimated income of around $3,000 per month for the recipient. The message closes with an invitation to schedule a meeting via Calendly.

Although the previous interaction took place earlier this year, the strategy remains the same, and more recent interactions suggest a more passive tone when offering these types of proposals. Likewise, it has been observed how some victims have responded to these messages.

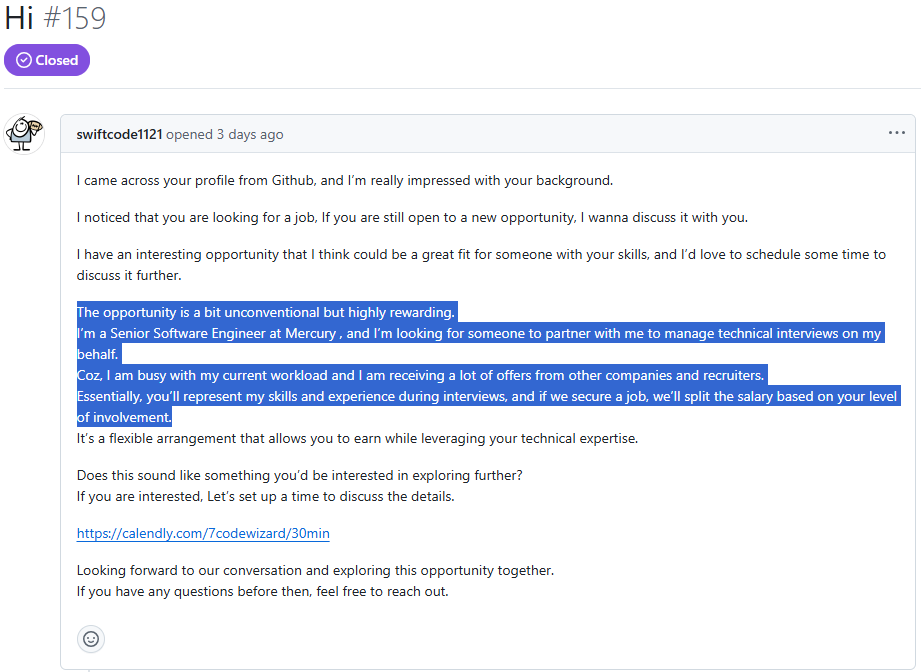

The following image shows that the account swiftcode1121 messaged someone on GitHub about a rewarding job opportunity in may 2025. The proposal involves the candidate representing swiftcode1121’s skills during interviews. If a job is secured, they would split the salary based on the candidate’s involvement level:

It’s important to mention that these GitHub profiles linked to DPRK IT Worker activity have been monitored for several months, and many of the patterns and red flags typically associated with DPRK IT Worker accounts are present. Additionally, these direct interactions, where various deals and arrangements to secure job positions are offered, seem to focus more on persuading the individual in order to achieve these objectives

6.2 Tactics and Methods Observed to Access Jobs

a. Social Engineering and Platform Positioning

DPRK IT workers create convincing developer personas and carefully manage their interactions to build credibility and blend into the global tech community. In observed interactions, they discussed personal interests like learning AI and recommended platforms such as CryptoZombies to study Solidity—a genuine area of technical focus.

When asked, they provided realistic GitHub optimization tips (e.g., customizing avatars, using project tags, writing profile READMEs), which reflected authentic platform knowledge rather than attempting to be friendly. Profiles are meticulously crafted to appear legitimate, with badges, activity levels, and detailed public contributions designed to enhance credibility and bypass initial scrutiny.

b. Remote Desktop Access to Evade VPN Detection

To avoid detection from IP-based geofencing, DPRK actors often request targets or collaborators to set up physical machines (such as laptops or desktops) in countries like the U.S. They then use remote desktop tools like AnyDesk or chrome desktop remote to connect and operate from those machines as if they were local users. This method could avoid the risks of VPN usage, which is increasingly flagged or blocked by platforms.

Motoki asked if I could purchase a PC for him, promising reimbursement or upfront payment. The purpose was to use that PC remotely and appear as a legitimate U.S.-based freelancer.

c. Social Engineering to Gain Access Through Proxies

These operatives frequently socially engineer individuals into becoming unintentional accomplices. They build rapport through casual conversation, offer mentorship, and eventually introduce requests such as:

• Allowing them to remotely use a device.

• Letting them use someone else’s identity to pass interviews and platform checks.

• Creating an account in your name while they perform all work in the background.

• Recruiting individuals to attend technical interviews and client calls on their behalf under false pretenses, as evidenced in the GitHub interactions.

• Promising financial incentives such as salary splits or freelance-style arrangements to make these requests more appealing and lower suspicion.

This form of deception makes it harder for platforms to detect the true operator behind the account.

d. Identity Masking and Borrowed Personas

Based on these chats it might be a lot more ways they could jump security controls or most regular ones. In this case to mask their presence, DPRK workers sometimes could ask individuals to:

• Create platform accounts using their real identity and verified documents.

• Attend initial video or voice interviews to pass KYC (Know Your Customer) checks.

• Hand over the account post-verification, allowing the DPRK worker to execute all work via remote access.

• Pose as the proxy for technical interviews, as seen in the GitHub conversation, where the operative sought a candidate to “represent their skills and experience during interviews”.

• Negotiate flexible deals where the recruited person’s level of involvement determines their share of the salary, adding a financial incentive to maintain the cover.

This tactic lets DPRK actors appear fully compliant with platform or client requirements while successfully evading detection and accountability.

e. Gray-Market Infrastructure: The “Laptop Farm” Model

A growing tactic involves the creation of “Laptop farms”—devices hosted by third parties in target countries but fully controlled remotely. These laptops act as physical nodes to access the platform ecosystem and simulate legitimate user behavior in restricted regions.

These schemes make detection extremely difficult, as activity appears to originate from within approved geographies using clean hardware and authentic accounts.

DPRK IT workers show high adaptability in circumventing location restrictions. Their use of remote access, social engineering, and identity laundering highlights a sophisticated understanding of platform enforcement mechanisms—and an ability to exploit the gray areas of trust and verification in the global digital labor market.

7. DPRK IT Workers Behind AssetX Scam: Applying for Grants on Polkassembly

There is a connection between the AssetX project proposal presented in Polkadot Assembly and the actor known as Motoki, along with their affiliation to bestselection18, highlights the broader operational scale of this DPRK-linked account cluster. These findings reveal a coordinated effort to exploit decentralized finance (DeFi) and freelance labor platforms for financial and operational gain.

Polkassembly is a recipient of treasury grants from Polkadot as well as Kusama for building the community’s go-to governance platform.

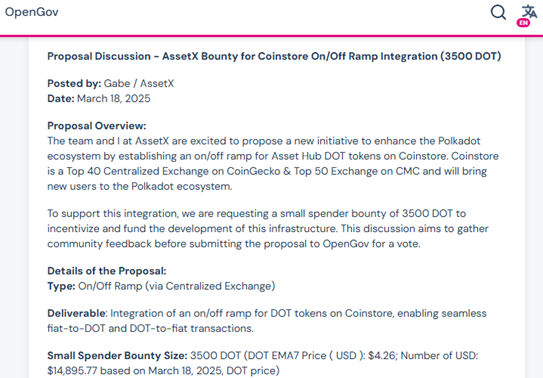

The activity linked to bestselection18 has been extensively documented. Based on their shared involvement in a project called AssetX—a decentralized exchange (DEX) designed for the Polkadot network—further coordination was confirmed.

This fraudulent project was presented on June 3rd, 2024, requesting $524,000 in funding to this Beneficiary Address: 14iULn6TYRmawsxazqR2xwWVuyDXc8ycGjg7ppJ15qVKctEN. It was ultimately rejected by the Polkadot team.

At the time of reporting, the wallet holds a balance of approximately 48 DOT (~$250.87). transactions show low-volume activity with most transfers not exceeding $500.

The individuals operating the GitHub accounts bestselection18 and Motoki are involved in additional fake projects, which remain under investigation and will not be detailed in this report.

7.1 New funding Requests on Polkassembly by AssetX

It is important to note that these cluster of DPRK IT workers has resurfaced under the same AssetX name—reusing identical networks, branding, and web links.

They are once again seeking funding within the Polkadot ecosystem, through a new proposal submitted on March 18, 2025, which aims to establish an on/off-ramp for Asset Hub DOT tokens on Coinstore.

However, the AssetX website linked in the proposal appears to be non-functional, and the individual submitting this new request identifies themselves as ‘Gabe’—still using the AssetX branding. The new funding request is significantly smaller, asking for approximately $15,000 USD. This smaller scope may increase its chances of approval.

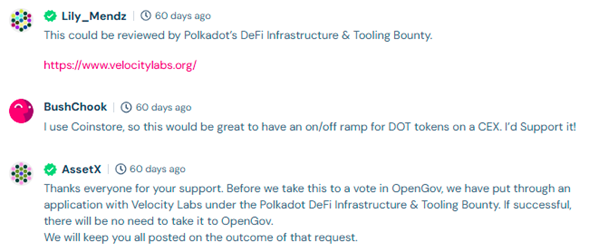

This same cluster—already flagged in earlier investigations—has openly admitted their involvement in other projects, as captured in their own public comments:

According to comments made by AssetX on Polkadot Assembly, the AssetX team also submitted an application to: Velocity Labs (Part of the Polkadot DeFi Infrastructure & Tooling Bounty.)

This points to a recurring strategy involving: use of false or synthetic identities, targeting of grant programs, various projects, protocol proposals, bounties, and other scenarios, using different aliases/handles to avoid detection.

The Polkadot Assembly team has been notified of this recurring behavior and is aware of multiple funding attempts by this group using the AssetX name. Despite previous rejections, the group’s continuous activity indicates a determined and adaptive infiltration strategy.

8. Conclusion

These conversations, part of the ongoing investigation, reveal several of the tactics and techniques leveraged by DPRK IT workers to infiltrate the U.S. job market.

This case involved direct interaction with a DPRK-affiliated operative, revealing not only a high level of operational sophistication but also a heavy reliance on social engineering. The human factor remains central to these campaigns — operatives frequently manipulate, persuade, or coerce individuals into enabling their fraudulent activities, sometimes even when those individuals are aware of the legal risks.

The investigation uncovers a persistent and well-coordinated campaign by DPRK-affiliated IT workers to infiltrate the global digital labor ecosystem, with a particular focus on platforms like GitHub, UpWork, and other developer and social collaboration spaces .These actors have refined a hybrid strategy that combines advanced technical tradecraft with psychological manipulation, enabling them to bypass platform security controls, exploit trust-based systems, and evade standard compliance mechanisms.

It’s also important to highlight the need for active cooperation from the affected project, company, or protocol. Sharing the profiles identified as DPRK IT workers is essential to prevent them from gaining access to other jobs or paid gigs within the ecosystem.

This is especially critical because many projects tend to treat the presence of a DPRK IT worker as merely a Compliance or KYC issue. In reality, these individuals represent a far more serious threat actor with specific objectives, requiring a different level of scrutiny and response. Unfortunately, in the Web3 industry, this is too often dismissed as a minor issue.

What’s even more concerning is that when these actors are discovered by third parties—often while they are already employed or receiving payments—internal processes within the affected organizations tend to downplay the situation. They create the illusion that everything is under control, when in fact, key internal procedures have been bypassed. This false sense of security overlooks the real nature and capabilities of the threat.

In many cases, these DPRK IT workers are not operating alone; they can share internal information with other groups linked to DPRK threat actors. In the worst-case scenarios, this could lead to multimillion-dollar exploits in blockchain projects, as has been documented before.

8.1 Strategic Takeaways and Recommendations

Understanding the tactics used by DPRK-affiliated IT workers is essential to anticipating and disrupting their infiltration of global tech platforms. The following insights provide an overview of some of their behaviors, and strategic goals, drawn from direct engagement

-

Persona Engineering: Fake identities, primarily using Japanese ones but occasionally others, paired with enhanced GitHub profiles, recycled profile images, and scripted interview responses to appear credible.

-

Remote Access Evasion: Use of tools like AnyDesk or Chrome Remote Desktop to control U.S.-based systems and spoof geographic presence, avoiding VPN detection.

-

Social Engineering: Building rapport, offering mentorship, or financial deals to co-opt individuals into creating or lending platform accounts.

-

Freelance Platform Exploits: Heavy use of UpWork, and open-source developer spaces to gain employment and build credibility.

-

Earn money by accessing grants, projects, or bounties: Attempts to extract large sums of money by submitting fraudulent proposals using fake identities and companies, often targeting Web3 sector initiatives — like the AssetX case on the Polkadot Assembly

To maintain persistent access and evade detection, DPRK IT workers leverage a resilient and obfuscated operational infrastructure. This framework enables them to operate across platforms while concealing their true identities and affiliations. Key components include:

-

Multi-account coordination also in GitHub with shared access to repositories (e.g.,

Motoki-kirbyAttack,bestselection18). -

Device-Based Deception (“Laptop Farms”): Remote operation of physical devices located in sanctioned-free regions (e.g., the U.S. or EU), allowing actors to appear as local users and bypass geolocation controls.

-

DPRK actors often rely on pre-scripted interview responses, disposable or mismatched email accounts, and synthetic personas crafted with convincing but falsified identity details (e.g., nationality, education, language fluency).

8.2 Awareness Tips & Mitigation Recommendations

- These recommendations are shared for informational purposes only. They intend to provide guidance and should not be taken as legal advice

For Freelance Platforms & Tech Employers:

-

Tighten KYC Verification: Enforce strict identity checks with recurring validation and multi-factor authentication.

-

Behavioral Anomaly Detection: Use machine learning to flag erratic access patterns, mismatched geolocation metadata, and suspicious account links.

-

Remote Access Monitoring: Alert for usage of remote desktop tools (e.g., AnyDesk, TeamViewer) in freelance workflows unless explicitly permitted.

For Developers and Community Members:

-

Verify identities during collaboration. Be wary of contributors unwilling to show genuine social presence or history.

-

Avoid being a proxy. Lending your credentials, device, or GitHub presence—even as a “favor”—can entangle you in illicit activity.

Check GitHub for Red Flags:

-

DPRK operatives exploit GitHub not just to showcase skills but as an operational hub for coordination, persona building, and infiltration. Platform security teams must go beyond traditional static indicators and adopt a behavioral and relational approach to threat detection.

-

Following/followers patterns – Accounts within the same cluster often follow one another.

-

Repository collaboration – Look for repeated collaboration across projects that lack genuine community interaction.

-

Avatar metadata reuse – Same or similar avatars across multiple accounts may suggest fabricated identities

-

An insistent attitude toward collaborating on projects, especially in Blockchain

Additional Red Flags to Monitor:

-

Minimal social presence or fake persona details (e.g., inconsistencies in nationality, language fluency, or professional history).

-

Reuse of identical profile sections (README files, skills, badges).

-

Connections to accounts already flagged for suspicious DAO or Web3 activity.

8.3 Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

GitHub Accounts:

-

github.com/motokimasuo

-

github.com/bestselection18

-

github.com/kirbyAttack

-

github.com/swiftcode1121

-

github.com/7CodeWizard

Email Addresses:

-

truepartner312@gmail.com -

motosimasuo@gmail.com -

jacksummers0822@gmail.com

Calendly url:

-

https://calendly.com/7codewizard/30min

-

https://calendly.com/davidcolman002/30min

Wallet Address:

- 14iULn6TYRmawsxazqR2xwWVuyDXc8ycGjg7ppJ15qVKctEN

(Used in the AssetX scam proposals on the Polkadot network)

- EVM: 0xe32418e9D4392155Dc20CE932Ff90D437a6E0C85

- SOLANA: 61mt2SSFNhpaiR4LCLadKoQwYuRUDvogM7ZFUJUwB8as

- BTC: 1JKM1dZ8nHHqqwVCXUMRN8r7zkYD6981y

(Payment address of Motoki Masuo)

This case serves as a vivid example of how nation-state actors adapt to economic sanctions by embedding themselves in the gig economy—exploiting technical platforms and human vulnerabilities alike. Likewise, it’s important to mention that this ‘cluster’ of accounts is actively trying to get hired, while also seeking opportunities to generate income, generally through grants, bounties, and development programs, mainly in Web3.